FOOD POVERTY AND POLICY IN IRELAND: A REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

Diarmuid D Sugrue UCD School of Medicine and Medical Science, University College Dublin, Belfield, Dublin 4, Ireland

ABSTRACT

Food poverty has emerged as a public health issue in the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland in the last decade. Dietary patterns have reflected the increasing numbers at risk of or living in consistent poverty. The aim of this literature review was to: quantify food poverty in Ireland, the effect it has on personal health, the implications for our health system, and to examine national policies aimed at alleviating it. The review focused primarily on research conducted by government, public health institutes, international bodies, all- island bodies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and charities. A definite trend in nutritional discrepancies across the Irish population was highlighted, with self-reported food deprivation higher in the lowest quintiles of income and social class. Children are particularly affected by food poverty, with 1 in 5 having reported going to school or bed hungry because of a lack of food at home. Major problems in the calculation of food poverty in the Irish population were found; for example many marginalised groups such as Travellers and asylum seekers have not been included in national surveys. There is currently no coordinated policy in Ireland to guide initiatives which might address social inequality in dietary behaviour. Given the changed economic landscape of the last 7 years, it is apparent that the official figures for food poverty in Ireland must be reviewed. The creation and acceptance of a standardised measure of food poverty is paramount in order to comprehensively understand the scale of the issue. An updated and coordinated all-island policy is urgently needed to prevent the impending tsunami of chronic disease caused by poor nutrition.

INTRODUCTION

Food poverty is defined as “the inability to afford or have reasonable access to food which provides a healthy diet”.1 This term has come to prominence in an era of plenty, where technology has enabled the mass production of food, at ever cheaper cost to the consumer. Much of the cheapest, processed food on the market is high in saturated fats, sugars and salt, and data has shown that those on lower incomes have a diet predominantly based around such foods. Living in poverty shapes dietary patterns; with food affordability, accessibility, availability and awareness being four main determinants.2,3 Thus, food poverty is a multidimensional issue encompassing economic, cultural and social inequalities leading to poor nutrition.

Food poverty has emerged as a social policy issue in Ireland and Northern Ireland in the last decade, with seminal studies by Friel and Conlon (Food Poverty and Policy) in 2004 and Purdy et al (Food Poverty: Fact or Fiction) in 2006 highlighting the issue in these respective jurisdictions. This was followed by Carney and Maître in 2012, who created a food poverty indicator for Ireland, designed to monitor food poverty trends on an annual basis.

The purpose of this review is to heighten awareness of food poverty as a public health issue in Ireland, and to critique what is being done to curb it. Part A quantifies food poverty in Ireland, the effect it has on personal health and the implications for our health system; Part B examines national policies aimed at alleviating food poverty. The review focuses primarily on research conducted by government, public health institutes, international bodies, non-governmental organisations (NGOs) and charities.

PART A: FOOD POVERTY IN IRELAND

1. FOOD POVERTY INDICATOR

Although never measured directly in Ireland, Carney and Maître constructed a food poverty indicator based on Central Statistics Office (CSO) figures contained in the annual Survey on Income and Living Conditions (SILC) between 2004 and 2010. This study was the first of its kind in Ireland, attempting to distinguish food poverty from other types of poverty, such as material deprivation, fuel poverty, financial and social exclusion. Using three basic deprivation indicators from SILC, and adding a fourth, a definition of food poverty was constructed. The indicators were:

Not being able to afford a meal containing meat or vegetarian equivalent every second day

Not being able to afford a roast dinner once a week

Missing at least one substantial meal over a two- week period due to lack of money

Inability to have family or friends for a meal or drink once a month

It found that 10% of the Irish population was living in food poverty, defined as those who had experienced one of the first three factors in the preceding month.4 This figure was higher for particular groups such as low income earners, with almost 1 in 4 one- parent families and unemployed persons in food poverty.4(PP28) Factors 1-3 relate to affordability as the indicator of food poverty. The fourth factor was not considered appropriate for the final composite measurement – it dominated a 2 out of 4 scale, doubling the percentage of those experiencing one or more deprivation items. Trends from 2008 to 2010 showed an increase in food poverty in this period.

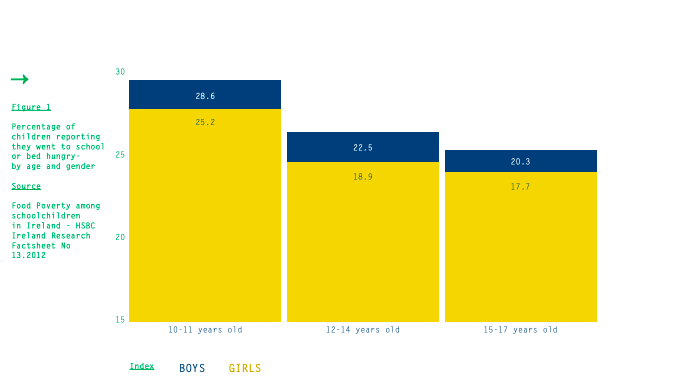

2. HBSC

Children are particularly affected by food poverty. Health Behaviour in School-aged Children (HBSC) is a multinational longitudinal study coordinated by the World Health Organisation (WHO) Regional Office for Europe. The Health Promotion Research Centre, based in NUI Galway, was invited to join HBSC in 1994, and has so far conducted four surveys of Irish schoolchildren (1998, 2002, 2006 and 2010).5 In 2010, it found that overall 21% of Irish schoolchildren reported going to school or bed hungry because of a lack of food at home. This had increased from 16.6% in 2006. In keeping with Carney and Maître’s study, it found that children from lower socioeconomic groups were more likely to report going to school or bed hungry (22.7%).6 However, food poverty in children was encountered across all social classes.

3. SOCIOECONOMIC VARIATION

Population-based studies worldwide have repeatedly shown that people from lower socioeconomic groups have less healthy dietary habits.7,8 The Survey on Lifestyle and Attitude to Nutrition (SLÁN) 2007 noted that consumption of foodstuffs advocated by healthcare professionals as being health promoting (such as low-fat milk, fruit, and white meat) is lower among the lowest socio-economic quintiles.

Conversely, consumption of fried foods at least four times per week was higher in every age group for men and women in this bracket.9 Factors contributing to this include affordability, accessibility, availability and awareness. Although SLÁN pinpointed education as the dominant socio-economic factor by which nutrients vary, Friel and Conlon concluded that socially disadvantaged groups display awareness of what constitutes healthy eating, yet are constrained primarily by affordability.3 (PP67) Given the inverse relationship between energy density of foods and cost10, it comes as no surprise that diets for those with limited resources are dominated by processed grains, fats and sweets. Although contentious, a recent meta-analysis from the Harvard School of Public Health comprehensively concluded that healthier diets cost significantly more than unhealthy ones in developed countries.11

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

Self-reported food deprivation was higher in the lowest quintiles of income and social class in each of the studies. Thus, there is a definite trend in nutritional discrepancies across the Irish population. Carney and Maître composed their index based on three food deprivation items as this was considered more appropriate than using each item individually, and more accurate as people may restrict spending in one area but may not in another.4(PP24) The specificity of the “unable to afford family and friends for a meal or drink” item was low, given how it augmented measurements. However, exclusion of this item prevented measurement of the social participatory aspect of food poverty.

The available data on food poverty in Ireland are now dated - Carney and Maître’s and HSBC’s figures both come from 2010. Likewise, although important studies, the figures contained in Friel and Conlon (2004)3 for the Republic of Ireland and Purdy et al (2006)12 for Northern Ireland are too dated so as to be accurate given the economic changes of the last decade. As previously mentioned, no direct population-wide analysis of food poverty has ever been carried out in Ireland – like previous studies, Carney and Maître used secondary data analysis, not designed to specifically answer their research questions. This limits the accuracy of the measures used. SILC does not measure access to food, nor the nutritional quality of that which is affordable.

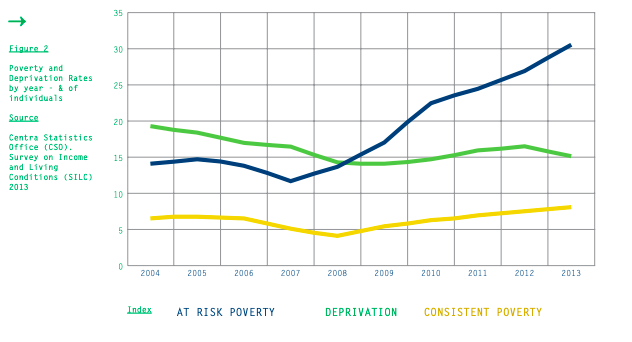

Vulnerable groups such as the homeless, asylum seekers, Travellers and those living in institutions were excluded from SILC 2010 and therefore the food poverty indicator 2012, as SILC is a private household survey. The Department of Social Protection commented at the time that this “limited” the findings. Carney and Maître also failed to indicate geographical variations in food inequalities across the country. With Friel and Conlon having identified these issues eight years previously,3(PP42) it seems there have been major, and as yet unrectified, structural problems in how food inequality in the Irish population has been quantified over last 10 years. According to the latest SILC (2013), the deprivation rate (two or more types of enforced deprivation) nearly tripled between 2007 and 2013, from 11.8% to 30.5% of the population.13 Given 3 of the 11 “deprivation items” are food related,4(PP14) and the inadequacies in research alluded to previously, Carney and Maître’s 10% figure must be reviewed.

HBSC is a school-based survey with data collected through self-completion questionnaires administered by teachers in the classroom. Schools from across the country are randomly selected and invited to participate. The strength of this research lies in its longitudinal nature and standardisation across participant countries, allowing direct comparison between jurisdictions. It also departs from previous Irish convention of quantifying food poverty by affordability, instead focusing qualitatively on the social and health impacts of food poverty on children.5 However, one must take into account the subjectivity of self-reported data, especially as this survey is carried out with young children, whilst also noting how random selection of schools could miss out on potential “black spots” of food deprivation across the country. Irish children are among those from 43 countries taking part in HBSC 2014. As of October 2014, nearly 10,000 questionnaires from 158 randomly selected schools have been completed for Ireland’s fifth instalment, and these data will offer a more up to date picture when they are published in 2015.

Carney and Maître provide the most comprehensive guide for assessing food poverty in Ireland, and it is certainly a persuasive and valuable document. However, like Friel and Conlon and Purdy et al (whose figures focused primarily on Household Budget Surveys), the indicators for food poverty were based on affordability of food. The study then could only allude to the more composite picture of food poverty incorporating accessibility, education, location and social exclusion. Unfortunately, this food poverty indicator stands alone in an Irish context; without detracting from its importance, it is therefore difficult to critique in relation to anything else.

EFFECT ON HEALTH

The role of diet in chronic diseases such as hypertension, coronary heart disease, diabetes, stroke, obesity, and certain cancers has been well documented since Ancel Keys’ “Seven Countries Study” was first published in 1963.14 There has been much debate in the interim as to what constitutes the optimal diet; nonetheless there is a general consensus that fresh fruits and vegetables, whole grains, lean meat and fish are preferable to processed food high in salt, added sugar and saturated/trans-fats.

‘Growing up in Ireland’ (2009) echoed this; 19% of boys and 18% of girls from professional households were overweight/obese, while 29% of boys and 38% of girls from semi- and unskilled social-class households were overweight/obese.16 International data reaffirm that the highest rates of obesity are found among minorities and the working poor.17, 18 Given that food poverty necessitates the consumption of low cost (and therefore) energy dense foods high in fats and refined sugars, and these foods increase the risk of obesity and cardiovascular disease, it is safe to say that food poverty is a major contributing factor to the high rates of obesity seen among lower socio-economic groups in Ireland. Thus, obesity is a socio-economic phenomenon with food poverty as a major risk factor.

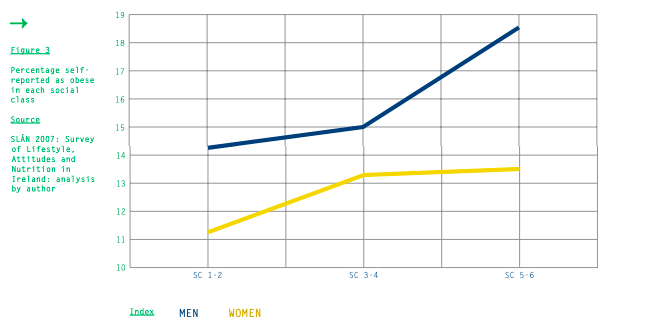

Ireland has not been spared from the global obesity epidemic. A comprehensive analysis of worldwide obesity prevalence carried out by The Lancet in 2013 found that 66.4% of men and 51% of women over 20 years of age in Ireland were overweight or obese.15 However, obesity rates are not evenly distributed across society; the Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes & Nutrition in Ireland (SLÁN 2007) shows a clear social class pattern for obesity in Ireland.9

Self-reported health quality is inversely proportional to food poverty.4(PP36) Children who reported going to school or bed hungry in HBSC Ireland 2010 were less likely to report excellent health and feeling happy about their lives. They were more likely to report current smoking, being injured, frequent emotional and physical symptoms and to have bullied others.6 This suggests that food poverty has consequences for both physical and mental health. It is clear that living in poverty directly affects food intake, and therefore health status. In their 2008 report for Combat Poverty Agency, Farrell et al reported that almost half (47%) of those who were consistently poor in Ireland reported they were suffering from a chronic illness, compared to just 23% of the general population.19 This reaffirms the inextricable link between food poverty and chronic illness.

EFFECT ON HEALTH SERVICE

According to a 2011 WHO report, non-communicable (chronic) diseases accounted for 88% of total deaths in Ireland.20 With an ageing population, this is set to rise. In 2009, the cost of overweight/obesity in the Republic of Ireland was estimated at €1.13 billion, and for Northern Ireland, €510 million.21 With poor diet a major factor in chronic disease, we are clearly in need of robust public policies to address it in order to reduce the burden on our health system.

PART B: POLICY

There is currently no coordinated policy in Ireland to guide initiatives which might address social inequality in dietary behaviour2; this despite the undoubted rise in food poverty over the last number of years, particularly since the financial crisis of 2008. Friel and Conlon’s “Food Poverty and Policy” (2004) is now ten years old, yet remains the most applicable policy document in this area. Following its publication, an all-island charity, Healthy Food for All (HFfA), was set up to address the issue, supported primarily by the Department of Social Protection (DSP), Health Service Executive (HSE) and SafeFood. The two pillars in addressing of food poverty have been community-led initiatives and state provision.

1. COMMUNITY BASED

Between 2003 and 2007, SafeFood – Ireland’s cross border food safety and nutrition body – funded a community-based project in Armagh and Dungannon called Decent Food for All (DFfA). This was the first initiative specifically aimed at tackling food poverty and obesity in deprived areas. It focused on educational sessions and practical workshops to overcome the barriers of financial access, physical access, and education.22 Similarly HFfA has coordinated and promoted community food initiatives since 2010. These include food growing projects, community food centres, education, food banks and meals on wheels. Projects are awarded a maximum of €45,000.2

The charity sector has taken on much of the burden of alleviating food poverty. Focus Ireland, Crosscare and The Society of St. Vincent de Paul (SVP) are all involved in the direct provision of food, with SVP alone spending €22 million on food and cash assistance in 2011.23 New charities such as Foodcloud use mobile apps to connect businesses with surplus food to charities who can distribute it.

2. STATE PROVISION

Food cost, welfare, and direct provision are all intervention targets. Employment is the central theme of poverty eradication policy in Ireland. However, with recent criticism that minimum wage falls below a “living wage”, it seems that employment alone does not prevent poverty. The benchmarking of welfare payments to average industrial earnings called for by Friel and Conlon and other commentators is idealistic and unlikely given the country’s finances. In terms of food cost, the reform of EU Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) under Irish Presidency in 2013 may lead to increased competitiveness and reduced cost to the consumer. The removal of restrictions on production volume of dairy products will reduce prices, whilst potentially driving other farmers towards vegetable or tillage farming. Although there is still an issue of food waste, €3.5 billion has been allocated to the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived for 2014-2020, to redistribute surplus food.24

Direct provision through the Schools Meals Programme operated by the DSP provides food services for disadvantaged children. Currently, this is implemented on a case-by-case basis, targeting those most in need, incorporating over 60,000 children. The long-term objective is that all school-going children should have access to meals in their school setting. Nutrition guidelines are in place for each meal with breakfast, lunch and snacks aimed at providing 25%, 33%, and 10% of recommended daily allowance respectively.25 Since 2007, the Food Dudes Healthy Eating Programme has been rolled out in primary schools across Ireland to encourage children to eat more fruit and vegetables. This has now been augmented by the EU School Fruit scheme, and the Department of Agriculture aims to have run the programme in 96.6% of all primary schools by the end of the 2014/15 school year.26

CRITICAL ANALYSIS

While the DFfA project was promising, it was carried out in a small an area and there was no follow up of participancts.. Although there was positive feedback from those who participated in the workshops, the level of understanding of term “healthy eating” actually decreased during the intervention period, and DFfA had no impact on the percentage of adults who were overweight or obese.22(PP53) Comparatively, HFfA has no data about how the community-based projects it runs have alleviated food poverty. Although charity may be beneficial, it is supportive not curative, and should not be considered a sustainable policy.

Resourcing the School Meal Programme has many potential benefits. Not only does this ensure that children receive a balanced food intake, but can educate them about what comprises a nutritious meal. A move towards universal provision ensures that all children benefit from enhanced nutrition without those who need it most being stigmatised. Secondary school interventions must also be considered. Ireland has subscribed to international agreements such as WHO’s Rio Political Declaration on Social Determinants of Health (2011) and EU-2020, aimed at reducing health inequalities. Healthy Ireland 2013 to 2025, the national framework for improving health and wellbeing launched by the Department of Health in 2013, recognises that “broad based policy approaches are needed [...] to ensure that health is an integral part of all relevant policy areas, including environment social and economic policies”.27 Healthy Ireland’s council includes representation from HFfA on the issue of food poverty. However much of this framework is yet to be implemented and, despite Carney and Maître’s stated aim of having their indicator used to monitor food poverty trends on an annual basis,4(PP11) there has seemingly been little follow up from government on this issue outside of the primary-school interventions already in place.

“Health Literacy” is a concept which carries cache in recent public health thinking; thus policies in Ireland have mirrored those worldwide which have tended towards educating the consumer, as opposed to modifying the food environment, to remove disparities in healthy food consumption across socioeconomic groups.10 Altering the food environment pertains to reducing the cost of healthy food while improving the nutritional value of cheap food. This would mean lobbying industry, with proposed measures including curbing advertising on foods high in fat, salt and sugar, and the introduction of a 20% tax on soft-drinks in conjunction with subsidies for healthy food options.28 However as Friel and Conlon pointed out, “the strength of the food and agriculture industry should not be undervalued in determining the food economy and market”.

CONCLUSION

The lead editorial in The Lancet in May 2014 warned how food poverty “lay at the heart of appalling health”.29 The same issue contained an open letter addressed to UK Prime Minister David Cameron signed by 170 members of the United Kingdom Faculty of Public Health, warning of the looming public health crisis, and calling for an independent advisory board to monitor nutrition and hunger status. Given the analogous crisis in Ireland, similar initiatives are required here. Firstly, it is evident that the creation and acceptance of a standardised measure of food poverty that includes all of society is paramount in order to comprehensively understand the scale of the issue. Secondly, an updated and coordinated all-island policy is urgently needed, coordinating numerous sectors: public health, social work, charity, education and local government.

Finally, this policy should not merely focus on education and community work, but on challenging industry to improve our food environment. With the impending tsunami of chronic disease caused by poor nutrition, resolving food poverty should be central to health policy in Ireland.

REFERENCES

01 Institute of Public Health in Ireland. Food poverty [Internet]. Dublin: Institute of Public Health in Ireland; 2011 [cited 2014 Oct 07] Available at: http://www.pub- lichealth.ie/healthinequalities/ foodpoverty.

02 Healthy Food for All. Food poverty [Internet]. Dublin: Healthy Food for All; 2014 [cited 2014 Oct 21] Available at: http://healthyfood- forall.com/food-poverty/

03 Friel S, Conlon C. Food poverty and policy. Dublin: Combat Poverty Agency; 2004 [cited 2014 Oct 30] Available at: http:// healthyfoodforall.com/wp-content/ uploads/2013/11/FoodPovertyAnd- Policy_2004.pdf

04 Carney C, Maître B. Constructing a food poverty indicator for Ire- land. Dublin: Department of Social Protection; 2012 [cited 2014 30 Oct] Available at: http://www. welfare.ie/en/downloads/dspfood- povertypaper.pdf

05 NUI Galway. Health behaviour in school-aged children (HSBC): background information [Internet]. Galway: Health Promotion Research Centre; last updated 2014 Jul 31 [cited 2014 Oct 21]. Available at: http://www.nuigalway.ie/hbsc/ hbsc_ireland_background.html

06 Callaghan M and the HBSC Ire- land Team. Food poverty among schoolchildren in Ireland – HBSC Ireland Research Factsheet No 13. Galway: Health Promotion Research Centre; 2012 [cited 2014 Oct 21] http://www.nuigalway.ie/hbsc/docu- ments/2010_fs_13_food_povertyjan.pdf

07 Darmon N, Drewnowski A. Does so- cial class predict diet quality? Am J Clin Nutr [Internet]. 2008 [cited 2014 Oct 21]. Available at: http://ajcn.nutrition.org/con- tent/87/5/1107.full

08 Konttinen H, Lähteenkorva S, Sil- ventoinen K, Männistö S, Haukkala A. Socio-economic disparities in the consumption of vegetables, fruit and energy-dense foods: the role of motive priorities. Public Health Nutr [Internet]. 2012 Aug 3 [cited 2014 Oct 21]; doi:10.1017/ S1368980012003540 Available at: http://journals.cambridge.org/ download.php?file=%2FPHN%2FPHN16_0 5%2FS1368980012003540a.pdf&code=49 9da552b0cb80a00e528452fc6608c7

09 Morgan K, McGee H, Watson D, Perry I, Barry M, Shelley E, Harrington J, Molcho M, Layte R, Tully N, van Lente E, Ward M, Lutomski J, Conroy R, Brugha R. SLÁN 2007: Survey of Lifestyle, Attitudes & Nutrition in Ireland: Main Report. Dublin: Department of Health and Children; 2008

10 Drewnowski A, Darmon N. Food choices and diet costs: an eco- nomic analysis. J Nutr [Internet] 2005 [cited 2014 Oct 21]. Avail- able at: http://jn.nutrition.org/ content/135/4/900.full

11 Rao M, Afshin A, Singh G, Mozaffarian D. Do healthier foods and diet patterns cost more than less healthy op- tions? A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open [Inter- net] 2013 [cited 2014 Oct 21]; doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2013-004277 Available at: http://bmjopen. bmj.com/content/3/12/e004277. full?sid=820d6e1a-280e-47a6-b8c5- 498bfa4657e3

12 Purdy J., McFarlane G., Harvey H., Rugkasa J. and Willis K. Food Poverty Fact or Fiction? 2006. Belfast: Public Health Alliance

13 Central Statistics Office (CSO). Survey on income and living condi- tions (SILC) 2013. Dublin: CSO; 2015 Jan 21[Cited 2015 Jan 27] Available at: http://cso.ie/en/ releasesandpublications/er/silc/ surveyonincomeandlivingcondi- tions2013/#.VMvGSv6sWSp

14 Seven Countries Study. About the study [Internet]. 2014. [Cited 2014 Oct 21] Available from http://sevencountriesstudy.com/ about-the-study

15 Ng, M. et al. Global, regional, and national prevalence of over- weight and obesity in children and adults during 1980–2013: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2013. Lan- cet 6736, 1–16 (2014)

16 Economic and Social Research Institute. Growing up in Ireland. Dublin: 2009 [cited 2014 Oct 30] Available from: http://www.grow- ingup.ie/

17 Paeratakul S, Lovejoy JC, Ryan DH, Bray GA. The relation of gen- der, race and socioeconomic status to obesity and obesity comorbidi- ties in a sample of US adults. Int. J. Obes Relat Metab Disord: 2002 Sep; 26(9): pp1205-1210

18 Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Johnson CL. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999- 2000. JAMA: 2002 Oct 9; 288(14):1723-7

19 Farrell C, McAvoy H, Wilde J and Combat Poverty Agency. Tackling health inequalities – an all-Ire- land approach to social deter- minants. Dublin; Combat Poverty Agency/Institute of Public Health in Ireland; 2008 [cited 2014 Oct 30] Available at: http://www. publichealth.ie/files/file/Tack- ling%20health%20inequalities_0.pdf

20 World Health Organisation. Noncom-municable diseases country pro- files – Ireland. WHO Europe: 2011 Sep [cited 2014 Oct 30] Available at: http://www.who.int/nmh/coun- tries/irl_en.pdf?ua=1

21 SafeFood. The cost of over- weight and obesity on the Island of Ireland – executive summary. Dublin: 2012 Nov [cited 2014 Oct] Available at: http://www.safefood. eu/safefood/media/safefoodlibrary/ documents/publications/research%20 reports/final-exec-summary-the- economic-cost-of-obesity.pdf

22 Balanda KP, Hochart A, Barron S, Fahy L. Tackling food poverty: Lessons from the Decent Food for All (DFfA) intervention. Dublin: Institute of Public Health in Ire- land, 2008

23 The Society of St. Vincent de Paul. Pre Budget Submission 2014. Dublin: SVP; 2013 Jun [cited 2014 Oct 30] Available at: http://www. svp.ie/getattachment/d93aed21- 5bdf-43ef-ad20-1519f9500078/SVP- Pre-Budget-Submission-2014.aspx

24 European Federation of Food Banks. European food aid [Internet]. FEBA; 2010 August [cited 2014 Oct 30] Available at: http://www. eurofoodbank.eu/portail/index. php?option=com_content&view=catego ry&layout=blog&id=26&Itemid=45&lang=en

25 Department of Social Protection. Urban & district school meals meals schemes [Internet]. Dublin: DSP; Updated 2008 Sep 30 [cited 2014 Oct 30] Available at: http:// www.welfare.ie/en/Pages/Publica- tion---Urban-_-District-School- Meals-Meals-Schemes.aspx

26 Department of Health. Healthy Ireland 2013 to 2025. Dublin; 2013. Available at http://www.hse.ie/ eng/services/publications/corpo- rate/hieng.pdf

27 Department of Agriculture, Food and the Marine. Strategy for school fruit scheme submitted by Ireland under Council Regulation (EC) No 1308/2013 & Commission Regulation 288 of 2009 for the 2014/2015 school year. Dublin; 2014 [cited 2014 Oct 30] Avail- able at: http://ec.europa.eu/ agriculture/sfs/documents/strate- gies-2014-2015/ie_national_strat- egy2014_2015_en.pdf

28 Royal College of Physicians of Ireland Policy Group on Obesity. The race we don’t want to win: Tackling Ireland’s obesity epi- demic. Dublin: RCPI; 2014 Aug

29 Horton R. Economic austerity, food poverty, and health [Editorial]. The Lancet 2014 May 10. 383(9929): 1609